This essay was originally posted to Reddit in July 2022.

It had been about a decade since I last read the original 1883 Robert Louis Stevenson Treasure Island, but after last month finishing for the first time and loving Black Sails, the 2014 – 2017 TV series that positions itself as a prequel to the novel and Long John Silver origin story, I moved the old book into the next available spot in my reading list to see how the two flowed together.

At first, I was harsh on Black Sails’ aspirations to be a prequel. Memorable book characters who obstinately share a past with Silver, such as Blind Pew and Black Dog, were nowhere to be seen in the show, and the opening chapters really only work if the reader assumes everyone from Billy Bones to the two aforementioned pirates and Silver himself is lying through their teeth about their relationship and history with Flint. That isn’t a huge stretch of the imagination, given how much of a theme self-aggrandizing lies were in the show, but having to fill in that headcanon at all still feels like a black mark.

And I do still think the Silver from the end of the show seemed too out of the game to return to the sea and piracy and Flint’s treasure so readily in Treasure Island. There’s a missing chapter in that man’s life no matter how you look at it. Silver’s dialogue in the book also has a very different flavour from the eloquence of the show version, even accounting for the ways the 130-year-old novel’s writing has aged. Try as I might in my head, I couldn’t quite get the book’s dialogue coming out show Silver’s mouth.

But once the novel reaches Skeleton Island, the details click into place. Black Sails may have eschewed 1:1 continuity for the bit part pirates of the opening, but it is a loving tribute to all the best part’s of the adventure’s climax.

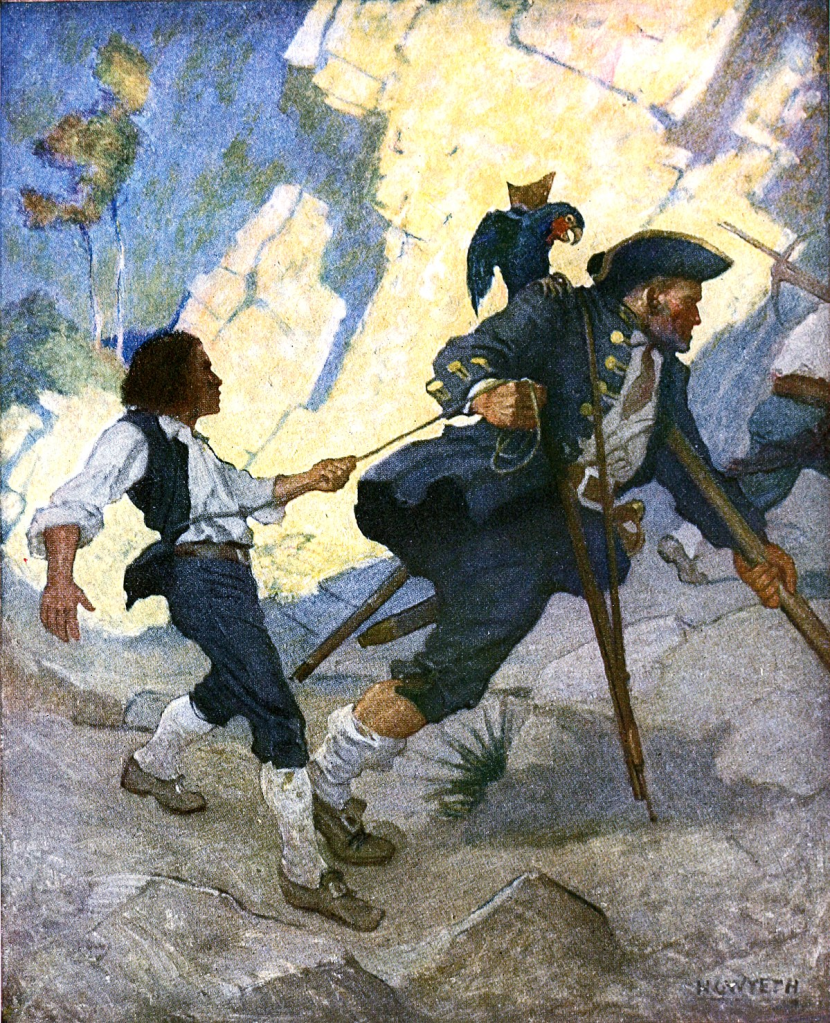

Long John Silver stands out from other literary villains for walking a fine line between mentor and antagonist, a character charismatic enough that you want to like him, even when you’re sure you can’t trust him. The kinship, betrayal, and alliance of convenience rekindling the kinship between Silver and Jim is everything surrounding Flint in the show writ small. When Jim blunders into the pirate camp and, with his back against the wall, spins his series of lucky breaks and failures of impulse control into a tale that plays him as the mastermind that sabotaged Silver’s whole operation, that’s what Black Sails was looking at. Silver says around that point that he sees a young version of himself in Jim, and I couldn’t help grinning when I read that, because I’d already been thinking it. Black Sails adds layers to Silver choosing to defend Jim against the pirates because you can see how genuine the resemblance between them is and understand where that sympathy comes from.

And the risks facing Silver, of the mutineers turning on him and voting him out, are of course reflected in everything Black Sails had to say about crew politics and the difficulties of power and leadership. Both stories show captains on a knife’s edge between keeping their pirates in line and keeping in their favour. That whole desperate section, where Jim observes Silver “keeping the mutineers together with one hand and grasping with the other after every means, possible and impossible, to make his peace and save his miserable life” is the connecting tissue between the novel and the show. It’s here in the middle and at the end, rather than from the beginning, that the two works find their unbroken line.

Given its target audience, it wouldn’t be totally out of line to call Treasure Island a young adult novel, though the classification obviously didn’t exist in its time. In that respect, I’d been expecting more of a difference in tone between in and the adult-oriented show. But Treasure Island pulls few punches in building its tension, especially in the pirate siege of the stockade and Jim’s fight with Israel Hands on the adrift Hisapniola. It doesn’t describe the violence in quite the same level of detail Black Sails chose to put onscreen, but the battles and death are starkly present. Combined with the above tale-telling, mentor-enemy dynamics and life or death politicing, I was pleasantly surprised by how natural a fit the two works turned out to be. Particularly after the continuity glitches from the opening set my expectations low.

I would love to see a Treasure Island adaptation, be it movie or miniseries, in Black Sails’ continuity, with at the very least Luke Arnold returning for Silver. While the dialogue is too aged to be used verbatim, the actions of and relationships forged by the book’s Silver are a perfect fit as an extension of the show’s version. I’m now hungry for Arnold’s take on John Silver realising he’s becoming to Jim as in many ways Flint was to him, and grappling with that fact as he tries to keep them both alive, but also weighing that objective against his original and far more selfish goal. I want this not just to have more Black Sails for its own sake, but because so much of the original novel’s core really is there in the show, and it would be a shame never to see those creators and actors cover that point of inception.

Leave a comment