R.J. Barker’s Tide Child Trilogy feels like a premise that could have been engineered by a focus group made up entirely of clones of me. In his afterword, Barker Cites Robin Hobb and Patrick O’Brian, the two authors I’ve read the most of over the past year, as major influences. On every conceptual level, I should be absolutely in love with these books, but the reality is that I only like them a lot. I will sing praise for most of this review, and these books have earned that, but it’s hard to shake the part of me that wishes they’d found that perfect, soul-touching personal emotional resonance to go with the tailor-made premise. Your mileage may vary if your expectations aren’t set as high by the elevator pitch.

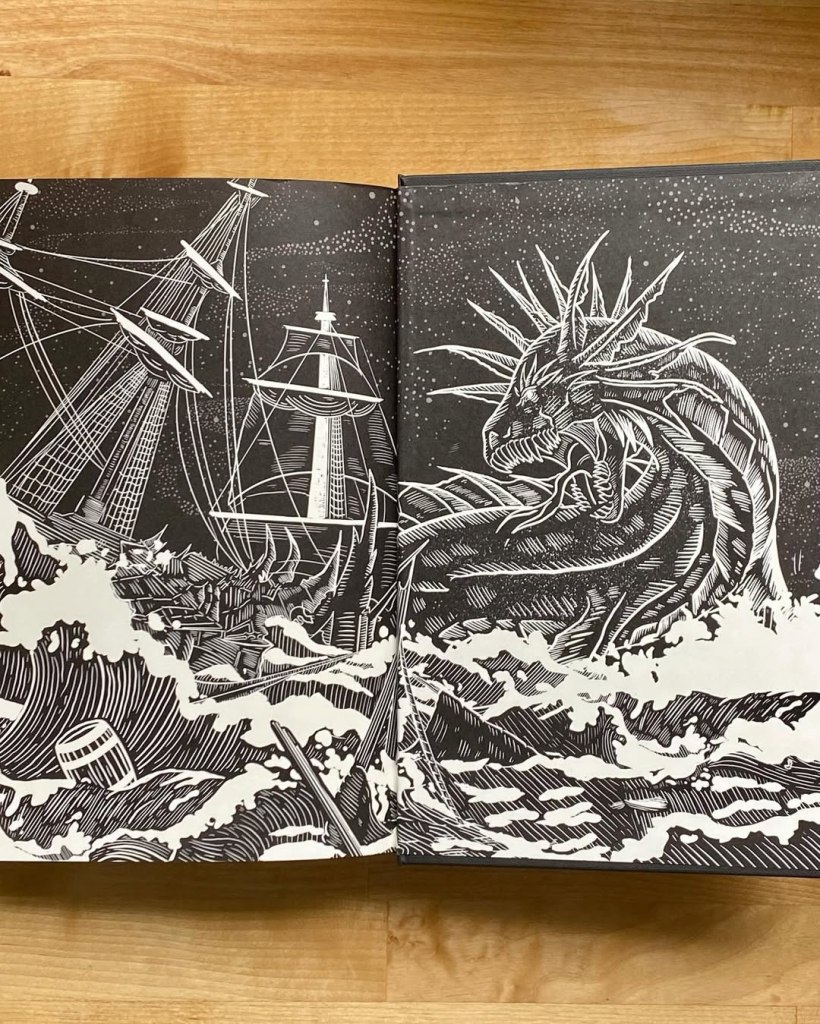

The series is set on an ocean world of scattered archipelagos where the Hundred Isles and the Gaunt Islands have fought an unending war facilitated by ships made of the bones of ancient sea dragons. These leviathans – the arakeesians – were hunted to extinction generations to go, leaving shipbuilding resources to dwindle, but recently a live one has been spotted in waters far to the south, and whichever side secures it will gain an insurmountable advantage. Former fisherman come condemned man Joron Twiner is raised from a drunken stupor by disgraced highborn woman Meas Gilbryn and made first officer on the ship she is to captain, the eponymous Tide Child, on a mission to find the last arakeesian. But Meas’s intentions aren’t the same as the hunters of the two warring nations.

The setting is the star of the show in this one, a harsh and unforgiving world presented immersively. The island environments allow little space for forests of lumber or grazing land for livestock, and this dictates what people eat, what they build with, and even what they make their clothes out of. The local religions, mythologies and superstitions touch everything from the language used in the narration to character motives and the ways battle plans are laid out, the rituals for protection and luck before action seen as unskippable. The warlike, pirate-viking cultures of the islands have ideas about gender and sexuality that shift whether on land or at sea and their own views of what traits are socially desirable. Even the knowledge that a ship was once a dragon changes the language used surrounding it. Ships are referred to with masculine pronouns, and have beaks and rumps instead of bows and sterns, spines instead of masts and wings instead of sails. It’s a world crafted with intricate thought put into the ways each aspect would change the ways people live and the cultural flow-on of those changes, and Barker prefers to drop you in the deep end of unfamiliar terminology and practices and let you piece together the meanings from context.

And I’d be remiss not to mention the Gullaime, a race of birdlike weather mages who are enslaved and forced to use their powers to move ships. These little guys are a charming and entertaining presence, and the discovery of their culture and history as Joron learns to treat the one on his ship as a sentient being is an undeniable highlight.

With maybe a hundred pages to go in the last book, I started to worry I wouldn’t get the deeper look into the history of the world that I’d really been wanting to see. It’s a setting with so many unique features it would have been a shame to wrap up without at least hinting at how and why it all ended up like it is, but there just didn’t seem to be space left for it. And that’s when Barker pulls off an impressive reversal, taking all the religion, superstition and folklore the series had built up and recontextualising it into a more tangible creation myth, giving the reader tools to understand what is metaphor for what (and which parts are surprisingly literal). There’s plenty of ambiguity left, but you get enough of a baseline for a satisfying ‘ohhhh’ moment as the info clicks into place. It makes me interested to someday do a reread and find out what smaller symbols I missed.

While the series is well-plotted and paced and the primary characters experience arcs that come full circle across its pages, none of them have the same surprising wow factor as the worldbuilding. Surface themes of leadership and crew-building play out alongside deeper ideas about honour, loyalty, balancing devotion to one’s own nation and culture against the good of the world, and how to change traditions without undermining the social pillars the traditions were made to reinforce. I enjoyed the journey and I liked the characters, but it never quite tugged at my heartstrings the way I hoped it would.

There is a little structural oddness between books when read as a set. The first one ends not with a cliffhanger, but with such a strong feeling of more to come that you expect the sequel to pick up exactly where it left off, and then you open the book and it’s been a year. It’s just different enough from what I expected to be jarring. You also find out in the recappy bits at the start of the first book about a very important, load-bearing romantic relationship between major characters that had apparently been happening during the first book. There were signs, on reflection, but they were far too subtle for the weight placed on the relationship from that point forward. I can respect Barker not wanting to write about romance or sex in anything but the most distant terms, but this one needed to be clearer to serve the narrative as intended.

For a nitpick among nitpicks, I also think the series and individual books could all have been titled better. The Bone Ships/Call of the Bone Ships/The Bone Ship’s Wake? These titles are all practically the same! I wouldn’t bring it up at all, except that the series has consistently great chapter titles. They’re all evocative and eye-catching without giving too much away as your eye rolls down the table of contents. Make ‘the Bone Ships’ the series name and give each book a title at least half interesting as its chapter titles, I say!

But I’d be doing Barker a disservice to linger any longer on that. The level of quality in the series remains absolutely consistent through to the end. Immersive worldbuilding, fantastic action, characters that are enjoyable but held a little too much at arms’ length to get really into their heads. I appreciated the desperate, against the odds, almost out of time tone that plans and manoeuvres increasingly take on as the series pushes towards its finale. There’s no boredom or wasted time, and major characters die just often enough that the tension never drops (although it is eventually noticeable that a few random hands among the crew will suddenly get names just ahead of a big fight because we need some deaths and can’t afford to sacrifice any of the main players just now).

The Tide Child is an easy rec. No part of it is bad. Some of it is excellent, but that makes me want more from the parts that are only good. Regardless of my personal unmet desire for a new hyperfixation, Barker tells an original story with skill and confidence that will entertain anyone with even a passing interest in fantasy and/or naval action.

Leave a comment